Interview

Antonio Scarponi • 27.06.2019

Democracy for yourself

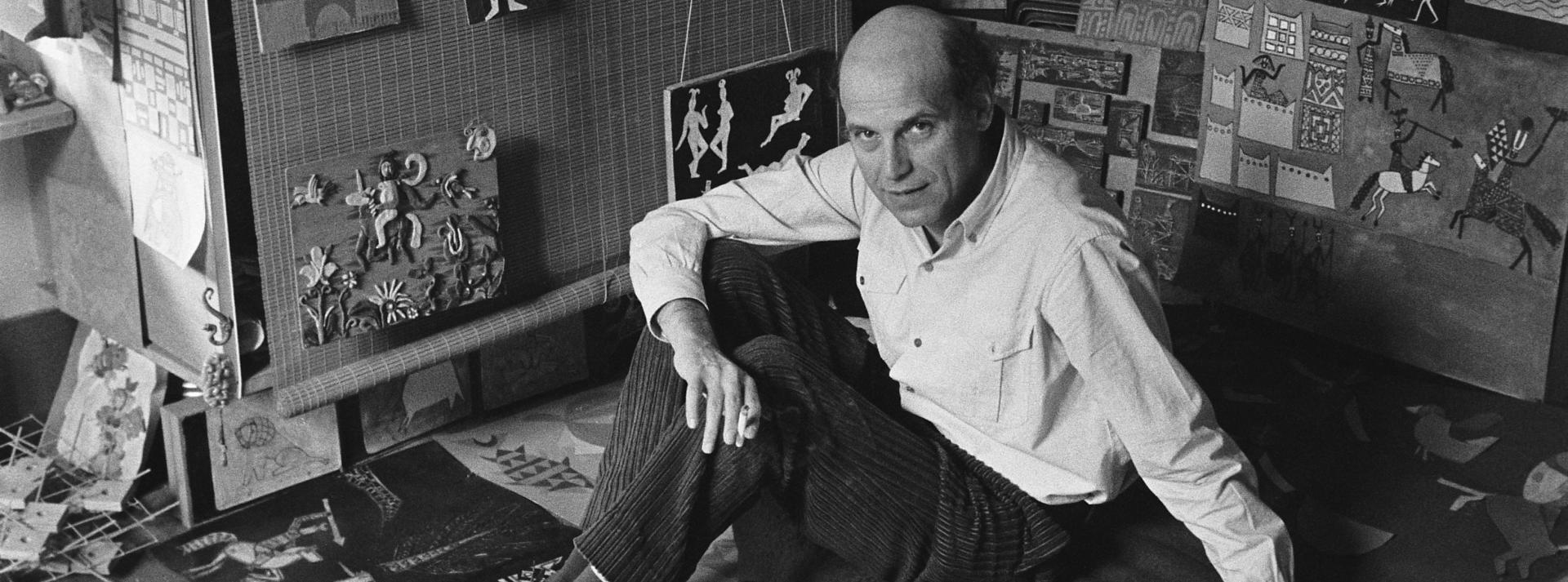

Yona Friedman is a Hungarian-born French architect, urban planner and designer. He was influential in the last century and is best known for his theory of mobile architecture. Today in conversation with Antonio Scarponi, he reflects on the future of dwellings at the age of 96.

Yona Friedman (Budapest, 1923), architect, was trained assisting among others, some of the most important conferences of Werner Heisenberg and Kàroly Kerényi. After the Second World War, during which he was involved in the resistance against the Nazi regime, he moved to Haifa in Israel, where he lived and worked for a decade. From 1957 Friedman lived in Paris. He taught at several American universities and collaborated with the United Nations (UN) and UNESCO. His immense literary activity extends from architecture to physics and from sociology to mathematics. Over the last few years, Friedman was invited to the eleventh edition of Documenta in Kassel and several Art and Architecture Venice Biennale. The last book dedicated to his Oeuvreis “The Dilution of Architecture”, (Yona Friedman and Manuel Orazi, edited by Nader Seraj, Park Books, Zurich, 2015).

AS: Your work is often described as “utopian”, while you argue that you’re a committed realistic optimist. Indeed, you fulfil a “here and now” vision with your work. What is the “future” for you?

YF: I think the future is made of the accumulations of many different “presents”. The way we speak of the future is an illusion, I have been around for a while, I think I can say that with a certain confidence! (Laugh)

AS: Last year I had the privilege of reviewing one of your most recent works, which is the culmination of a lifetime for Domus Magazine: Roofs (Italian edition, “Tetti”, Quodlibet, 2018). I am fascinated by this book, and not only because it contains so many years of research, fieldwork and study, but also because it is all provided with absolute lyricism. I like the clarity of the challenge: how to build roofs, for yourself, by yourself (even with bare hands) in the middle of nowhere. In a way it allows us to connect with the essence of the act of building. It reminds me of the famous novella that Banham used to talk about the two archetypes of architecture, “the hut” and “the campfire”: a group of hunter warriors find themselves in a middle of a clearing at sunset when it is too late and too dangerous to return to the village and they have to decide whether to build a hut with the wood available in their surroundings or start a campfire in order to face the night. According to Banham, this dilemma represents the two archetypes of architecture: the hut, the built form and the campfire, the unbuilt form. Do you think “a roof” represents the essence of a dwelling?

YF: The essence of dwellings belongs to humanity as a whole, as an ecosystem, and this goes far beyond the four walls. It has always been like this; dwellings did not change significantly in the “animal nature” of human beings. Technology can change social structures or maybe infra-structures; it is part of our ecosystem. A roof is a part of an ecosystem, humans build ecosystems. Ecosystems change. I have the impression for instance that today, Instagram is more important than MOMA as ideas circulate much faster there and it is seen by far more people with much less mediation than in a museum. Now what is essential to bear in mind is that these two realities are interwoven, one does not exclude the other, or rather, one includes the other, in some cases even amplifies it. Knowledge today is produced and shared in a new way. This also influences how we can learn about building a roof or how to start a campfire; how we can live underneath or around it and even the way we look upon it.

AS: I have read in an interview that as a young architect you were “granted” a rendezvous with Le Corbusier, the first time in 1949 and then again in 1957. In the interview, you say that in 1957, you showed him your plan for mobile architecture and that he said, «I would never do it, but you have to do it! » I am not sure how many masters I have met who would have said something like that to a young architect at the beginning of his career. How hard was it for you to follow your gut instinct and do your thing when everything started?

YF: Yes, this was very typical of him. He did not “approve” ideas beyond his own. He was absolutely right about that. But he thought that people working along different lines might also have a reason, so in a way, he encouraged me to keep developing what I was working on. It is like saying, «I disagree, but I can encourage you to get out there and find out if the old chap is right». I think he was right, but in the sense that I had to find out myself, and of course, my conclusion is that he is wrong! However, I had to do what I had to do. Having one’s ideas is always a form of resistance. It starts with childhood. It is important to encourage the “resistance” of younger generations. It is all about courage. To have courage, to be brave means knowing how to lose before even beginning, but anyway, start, do it and go all the way, no matter what. Le Corbusier won; I have won. We did our thing, no matter what. I encourage younger talents to do the same and measure their courage against the fear of failing and against failure itself! With this attitude failure does not exist.

AS: Did you have any connection or exchange with the Situationists in Paris at that time in the ‘50s? Constant, for instance, was also working on an idea of nomadic architecture (New Babylon) at that time, which resonates with your idea of Mobile Architecture.

YF: I had no contact with any of the Situationists, nor with Constant when I was working out L’Architecture Mobile. Constant contacted me after he had read the pamphlet I had drafted then. Afterwards, we met in Paris, in my home. I think it was in 1961 and later we sort of became friends.

AS: I have the impression that Eduardo Paolozzi in the ‘50s was the bridge between the US, Paris and London. I know he was in contact with the Situationists and he was obviously very active in the Independent Group in London. He brought the ideas of Buck Minster Fuller as well as the American sub-pop culture in which Bucky’s ideas were circulating at the beginning. Afterwards Hamilton and McHale coined the term Pop-Art within the context of the Independent Group. Were you somehow in contact with Eduardo Paolozzi then? Were you interested in the ideas of Fuller at that time? I know you had a significant influence on Peter Cook and other members of Archigram while they were still studying.

YF: I never knew Eduardo Paolozzi. With Bucky Fuller I had friendly relations through letters, then we met personally in 1962 in Essen. Yes, I had met Peter Cook and others when they were still studying, but this is what I have learned from Corbu: take a position and encourage others to develop other positions.

AS: I have learned from you that architecture is made of hope more than bricks and mortar. I have just finished reading a novel by Romain Gary, “The Kites” (Les Cerfs-volants, is the original title). In my opinion, this novel describes this idea of “imaginative resistance” very well, which is close to where I also place your work in my imaginary library. Let’s imagine designing a kite to fly high in a clear sky so that it could help us to have an opinion, or a hope, for tomorrow. I would like to ask you to pick five keywords on dwellings today which in your opinion can frame an understanding of a “new today”.

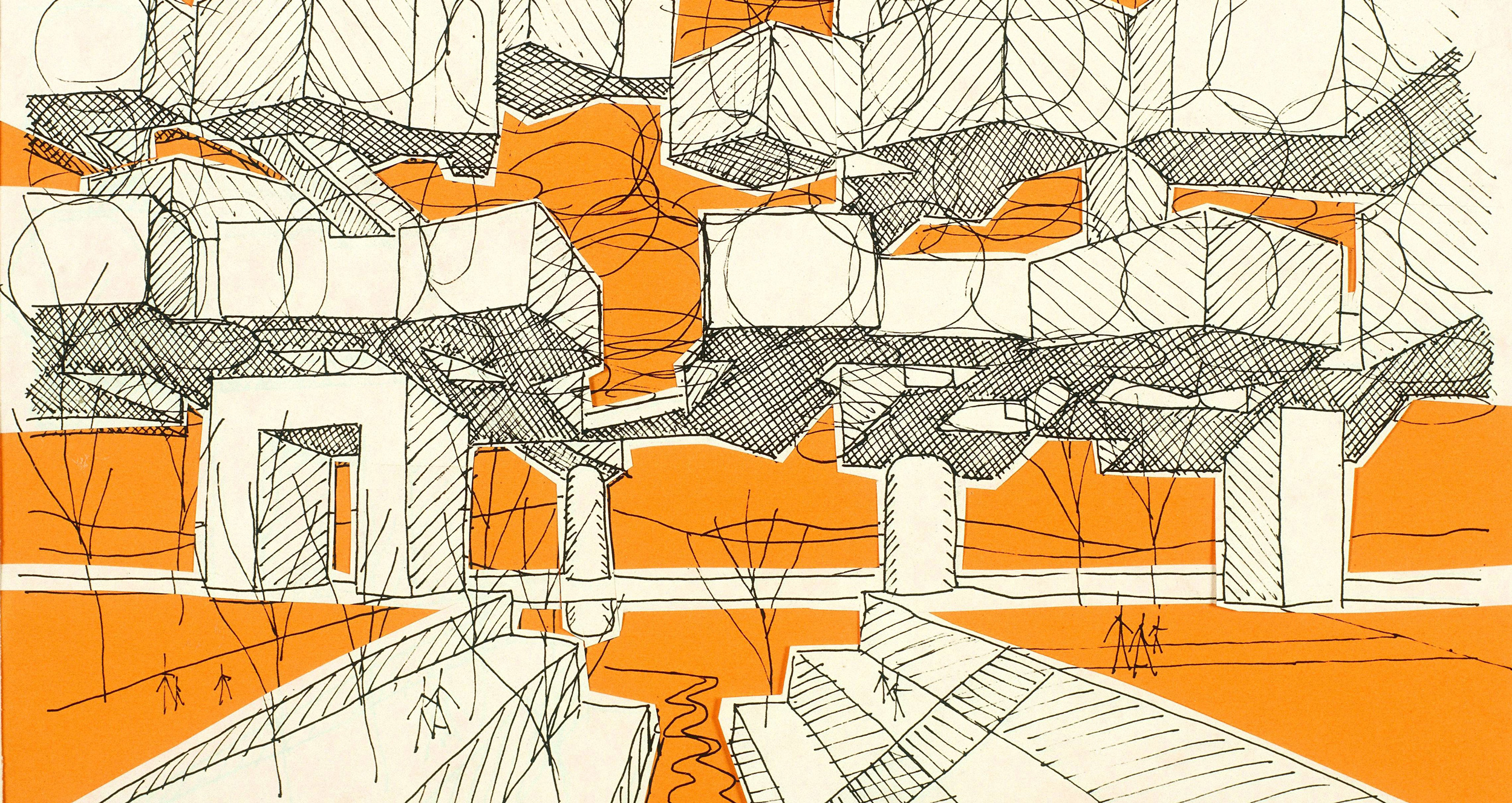

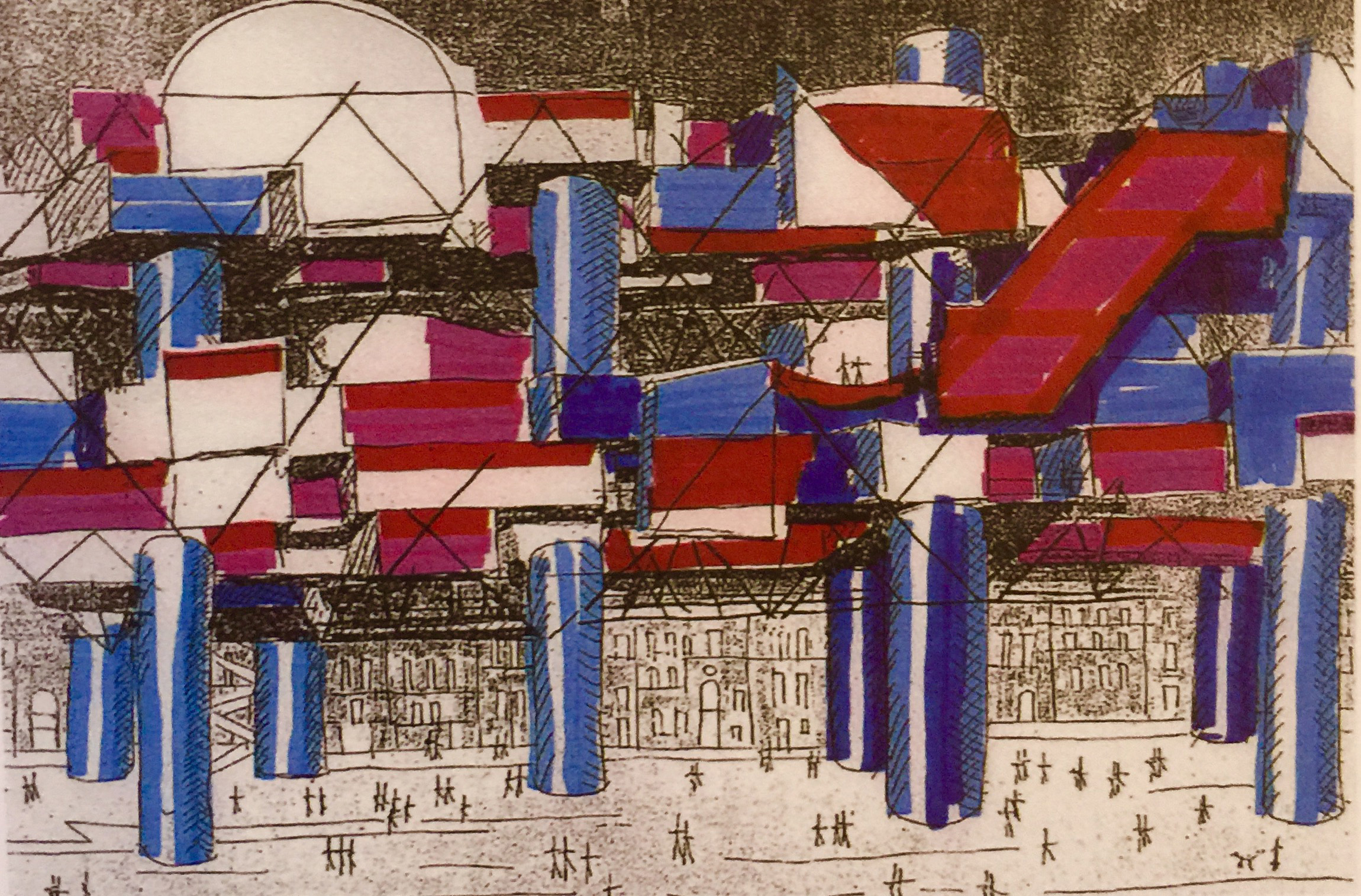

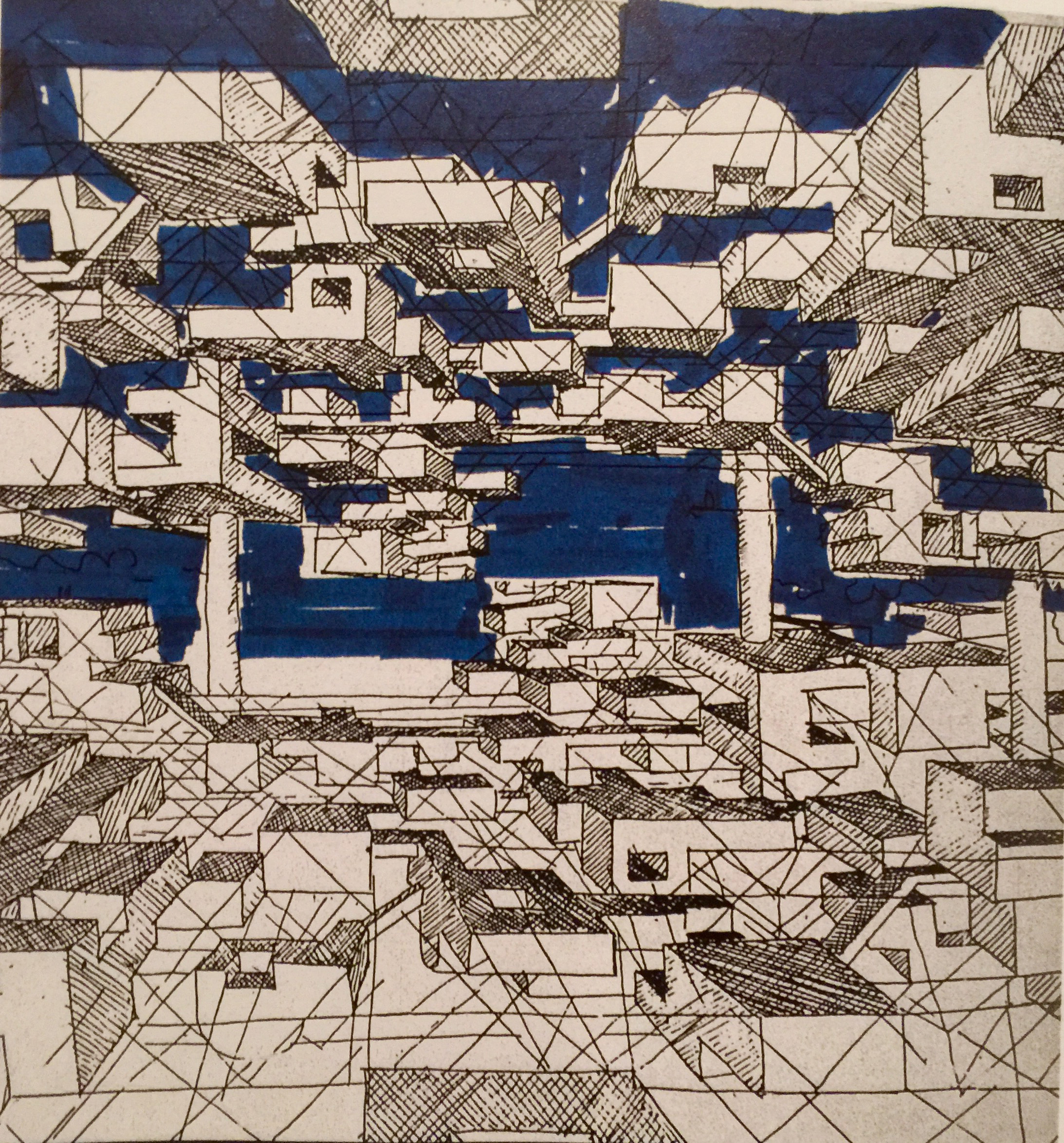

YF: Maybe if I tell you what I am working on now, I might indirectly address your question. I am currently working on the idea of “Global Biosphere Infrastructure”, it is a paper and drawings I presented last year at the Kiesler Foundation that frames the concept of “Democracy for Yourself”:

• Planning for Yourself

• Building for Yourself

• Maximum Autonomy

• City Infrastructure and Object at home (Cloud Infrastructure);

• Trees (very important).

I guess this can be the brief to design my kite.

AS: In your vision, where does “democracy” meet “autonomy”? Don’t you think that these two words contradict each other?

YF: For me “democracy” is a particular pattern of our everyday behaviour, evident in all of our actions as human beings. Even the way we talk now is fundamentally an act of democracy, while “autonomy” for me means the possibility to empower decision-making by yourself. Technology offers only the means for it. If you like, it’s the string of the kite: it anchors it to the ground but allows us to see it and feel the wind. Maybe we can stretch this metaphor even further and think of architecture as a “kite”. Architecture should be “mobile”, and trees are the stable, fixed environment. They are the landmarks of the new city, sort of natural monuments eventually helping orientation.

AS: Do you think that natural collaboration and participation are based on the gap between “democracy” and “autonomy”? Or, in other words, what do you believe is the role of the “other”?

YF: It is a fundamental part of the ethical code in practice. Without “the other”, a kite won’t fly. The “other” is the wind, ideas need be shared to fly, even if we know that everything will touch the ground sooner or later.

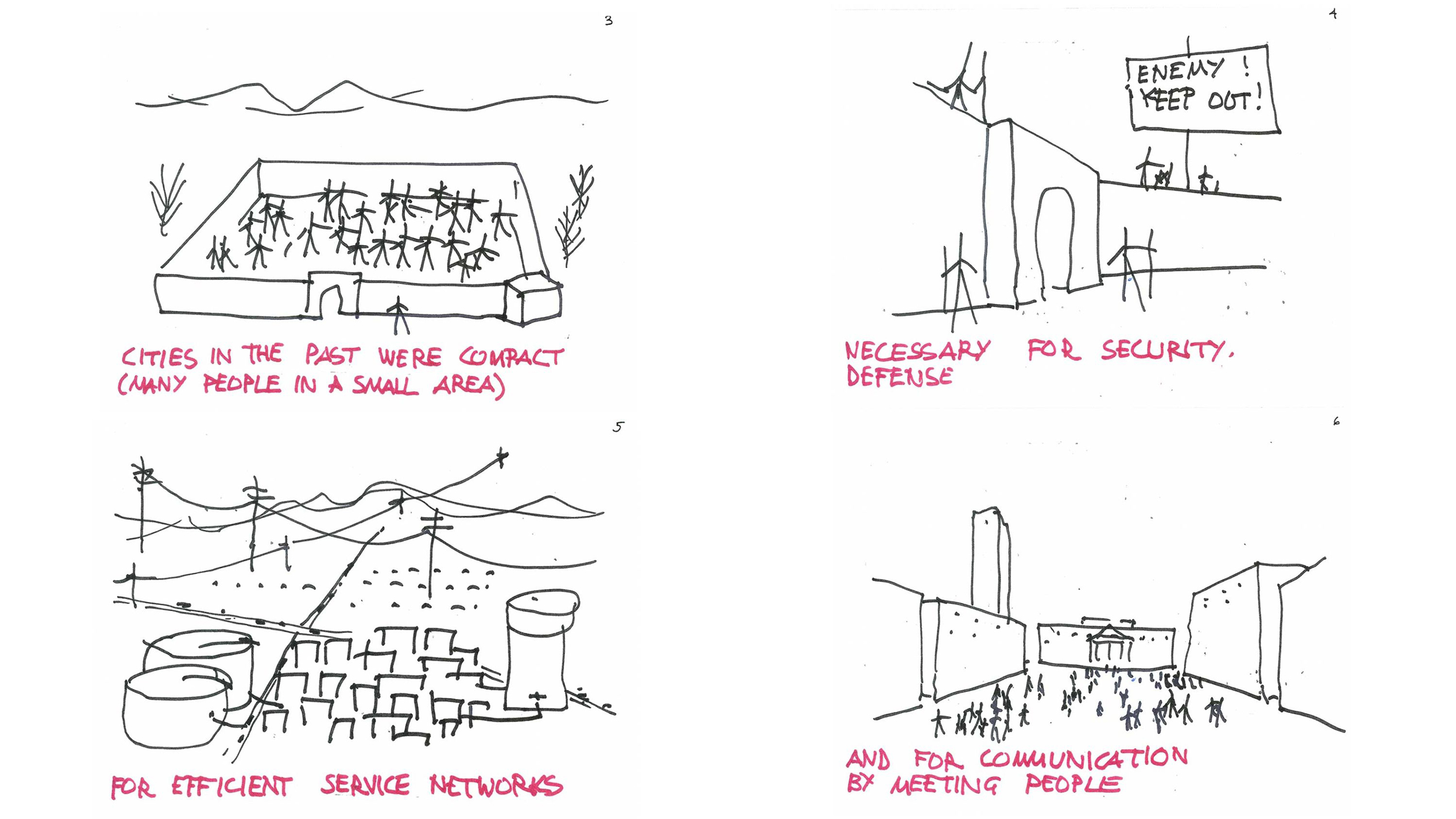

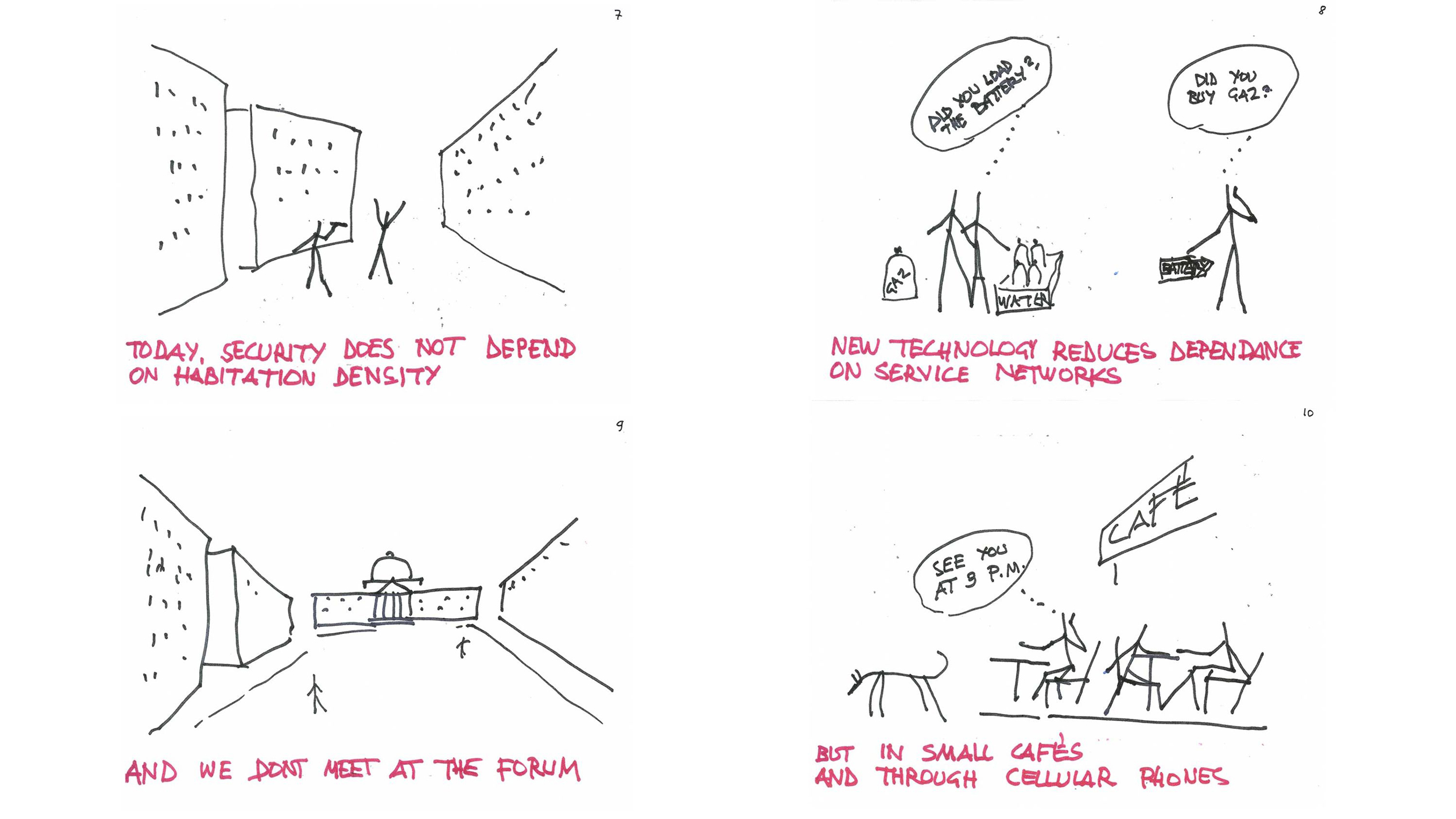

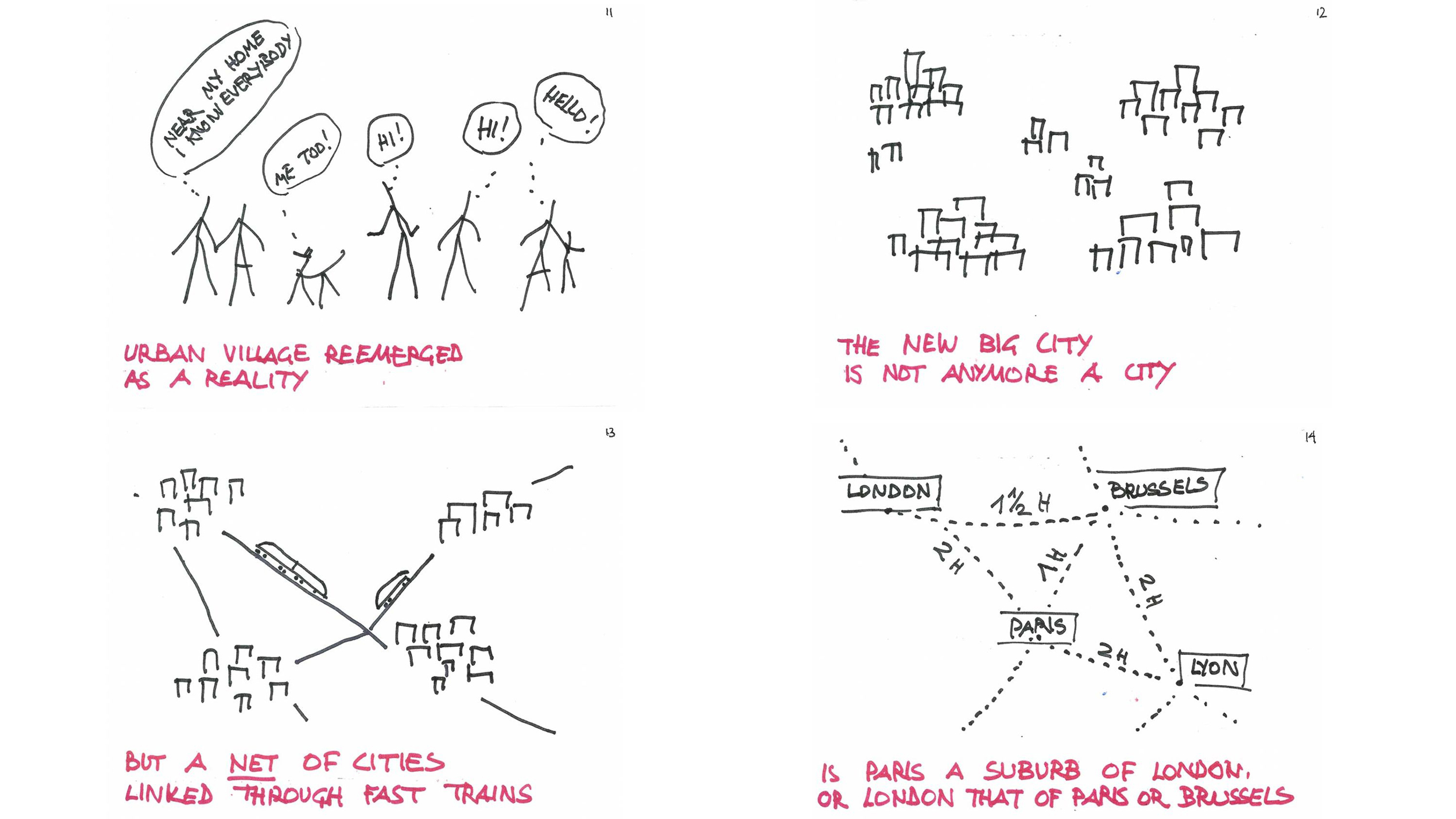

AS: The first book of yours that I read was Utopies réalisables. It was in 2003, when it was published in Italian with Quodlibet in its new edition. I devoured it. There is a point at the end of your book that still makes me jump out of my chair. You argue this equation: Agriculture = sedentary; City = nomadic. I jump out of my chair because it reverses a collective imaginary where nomadism belongs to erratic, untouched landscapes and introduces a counter-intuitive vision in which nomadism is in reality a large-scale event, happening within a cluster of infrastructures that we call cities. This view is in line not only with a vision of the true nature of cities, which are infrastructures made of, and for, migrants (in a broader understanding of human migration), but also with a growing trend that it is observed worldwide: an ever-increasing number of people living in cities (32%, 2018 versus 28% in 2016), who stated that they “feel more at home” in specific places out in the city than in their apartment where they are actually living. Now, let’s take this survey for granted. We do not have the means here to discuss the legitimacy of such an assertion. Besides I am not sure if life and feelings can be reduced to statistics. However, I guess it shows that the emotional idea of the “home” is increasingly “exploded” into a broader context of situations, public spaces, events, independently from where someone stores their clothes. The feeling of the home is technically, or potentially, “everywhere” and I suppose nowhere at the same time. I do believe that this survey does have an impact but more into the imagination than as a real “fact”. You have explored this idea since the early days of your career, already projecting in the 50’s the possibility that technologies were already available more than they were permitted. Do you think that contemporary societies are more inclined to “walk the talk”?

YF: I do not know, I am an architect, not a fortune teller! (Laugh)

Nowadays contemporary architecture is a pure expression of economic capital. It was also like that in the past, of course, but the “economic capital” also represented “symbolic capital” in some respects. Spiritual capital if you like. In an age where economic capital IS the symbolic capital, meaning that the economy does not stand for much else apart from itself, symbolic values are dissociated from physical forms. I suppose that makes us increasingly symbolic nomads looking for the authenticity of true living, and we move from the supposed quality of things towards the quality of life. The city dissolves with mobile infrastructures and detectors are ever smaller, and with them, we tune our mood like we used to do with the radio to catch a clear signal, to find our home feelings without the home, away from the four walls.

In a way, mobile infrastructure makes traditional architecture obsolete. It frees the disappearance of bourgeoise and the spaces in which it was used to celebrate itself. This is not only affecting the home, but also working spaces. As a result, cities are becoming the infrastructure of nomadic tribes that follow data flows instead of “song lines”.

The home is no longer a place but rather a feeling dispersed in many places in time, something that we continuously seek, finetuning our microdevices as diviners, by ourselves, for ourselves.

AS: Speaking of the city as “infrastructure” or city-infrastructure (maybe in relation to the idea of the “cloud-infrastructure”) when, in your view, does the city “dissolve”, disappear? I refer here to your last book: “The Dilution of Architecture” (with Manuel Orazi, edited by Nader Seraj, Park Books 2015).

YF: I think we can look upon the city as the place where we project our dreams and our desires and where we share them with others. I think it is not the city that disappears or dissolves, instead there is the disappearance of an old notion of infrastructure where networks are no longer, or not only, supported by physical infrastructures but they are substituted by household equipment such as mobile phones, solar captors, rain collection systems, micro antennas. All of a sudden, the city became obsolete in its traditional form, as we know it, theoretically unnecessary. We are witnessing the dissolution of the working place as we know it, we are seeing the demise of the home as we know it, we are witnessing the dissolution of institutions. I think there is the possibility of a new maturity of humanity and for architecture, autonomous, free, democratic awareness.

AS: Are these the premises of a Global Biosphere Infrastructure?

YF: Yes. But we need to bear in mind that trees are important.

Antonio Scarponi

Antonio Scarponi is an architect and designer, founder of the Zurich-based Conceptual Devices (www.conceptualdevices.com) practice, where he pursues research of design as a form of freedom. He studied Architecture at Cooper Union, New York, and at IUAV, Venice. Among others, he is the 2008 winner of the Curry Stone Design Prize. He collaborated with many international magazines, including Domus, Abitare, Wired. He taught and lectured in several European and American universities and he is currently a faculty member of the Zurich University of the Arts. His work has been widely exhibited in several design museums and galleries. In 2016 he took part in the XV Venice Architecture Biennale. He is the author of ELIOOO– an instruction manual about how to hack the IKEA global distribution infrastructure to create a device to grow food in your apartment.