Oliver Herwig • 12.06.2018

Will mini houses ease the housing shortage?

Built quickly and ultra-light, mini houses are very much in vogue. But are they tried and tested to deal with the housing shortage? A large number of bonsai plans are rubbing salt in the wounds, but the central question remains: How do we want to live in the future? Speculation.

What does the apartment of tomorrow actually look like? «Transportable», say some people, sip chai tea and then pack their notebook and pad in their backpack. «Augmenting», whisper others and push their Smartphones across the breakfast table. Calorie counts and nutritional value tables flash up on the screen as soon as they hover over muesli and yoghurt. It is true: We rent something via Airbnb all around the world, carry our office in our trouser pocket and experience technology as a third skin, which of course connects to our loved ones, while our home is basically still what it was a century ago: A pile of concrete, tiles, cables and pipework, in which we spend a large proportion of our lives.

Now the property economy is not a higher level of mathematics. It sells what sells, in other words houses and apartments, whose designs change as little as fashion in North Korea, apart from the fact that a kitchen/diner has been popular for a while and tomorrow there will be a bath in the bedroom wherever possible.

It sounds paradoxical. At first sight we live more colourfully and easily than in the past, but in fact living is increasingly becoming a product, which can be precisely defined and produced.

Naturally statistics cannot lie (;-). Already ten years ago singles already accounted for almost one-third of the residential market, and in major cities one- and two-bedroom apartments now dominate. A large, prestigious apartment is becoming the obsolete model of a generation of pensioners, while an increasing number of couples are voluntarily shrinking their space so that they can afford a second apartment in the sun.

This makes mini houses sound pretty interesting. Two years ago the Berlin architect Van Bo Le-Mentzel, who had already come to notice with his provocative Hartz-IV furniture, offered a bonsai house of 6.4 square metres, the «Tiny100». It’s transportable. Inside there is a small kitchen and a sofa. The ladder leads to the mezzanine bed with the shower-toilet and kitchen underneath. In other words an upgraded adolescent’s room. «Dream or nightmare», was the title of the article in Der Stern. It immediately became clear: Here it’s no longer about design, it’s about getting straight to the point: How do we want to live – namely as a society? With his two metre wide home model Van Bo Le-Mentzel is propagating both restriction and efficient use of resources as well as distributional justice.

Tiny100

Photography top-down: Tinyhouse University, Philipp Oberkirchner, Daniel Hofer

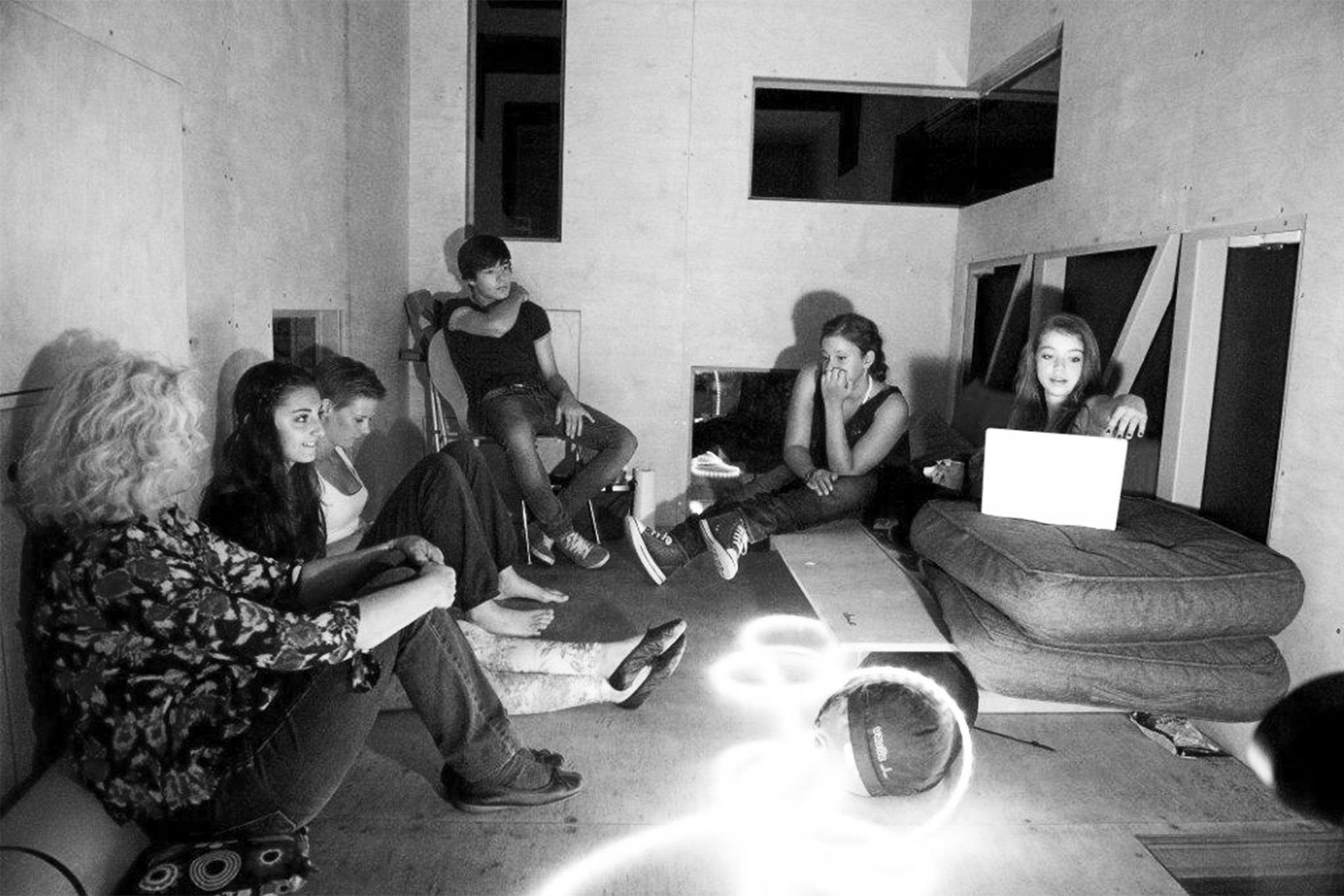

It’s therefore appropriate that Mia Behrens and Johanne Holm-Jensen, two young Danish architects, are taking the next step. Their «Building Blocks» project combines the latest manufacturing techniques (CNC milling machines) with the benefits of the open-source community: As soon as a draft was published it’s «in the public domain and freely available», it says, in other words, «for everyone to use, change and share.» In future it will be possible to «download a house, adjust it, build it and continually improve it over time.» Suddenly house building is latching onto the comprehensive modernisation of our times and is leaving its skilled trade context, which thinks in single figures and develops a specific solution on site for every problem. This could be regrettable because there is also a risk that the special features of architecture will get lost along the way, in view of the exploding number of tenants and the extreme housing shortage, but citizens should also ask whether we still can (or want) to afford individual buildings.

«Building Blocks» came about during a six-month stay at SPACE10. The vision: affordable, sustainable and modular housing for everyone – and therefore the opportunity to democratise the house of tomorrow. Everyone should «download the open-source design from everywhere, adjust the house to different landscapes, terrains and cultures, make the necessary parts locally and be able to put the house together relatively quickly and easily.» The modular prototype made of FSC-certified plywood is 49 square metres in size and can be adjusted to the requirements of the potential house builders. The dimensions are selected in such a way that at least in Denmark «no permit is necessary from the local building supervisory authorities.» By using a CNC milling machine and inexpensive building materials, Mia Behrens and Johanne Holm-Jensen could keep the costs down to precisely € 8,000. That’s an unbelievable € 163 ($ 192) per square metre.

Building Blocks

Photography: Niklas Adrian Vindelev

Visualisation: Mia Behrens and Johanne Holm Jensen

Their manifesto also reads like a sharp change of era. It shows how the attitude of architects is changing, moving away from the context-specific and individually designed house («architecture of the past») to a modular system: «We are continually building larger, faster and more affordably to optimise processes and minimise costs and have fewer opportunities to work meticulously on every detail of a building.» Naturally this is not a complete swan song for old traditions because in the final analysis Mia Behrens and Johanne Holm-Jensen want to investigate how and whether «modern manufacturing technologies can be combined with skilled trades». And yet they are offering a toolbox, which makes architecture available to everyone. Is a Spotify for three-dimensional things being created here? At least everyone has to lend a hand. Design problems still need to be solved: such as drainage for rain water – a task that Mia Behrens and Johanne Holm-Jensen have consciously left to the community. This is also new territory: Here is the beta version, so make something of it.

And because even such a project cannot survive without inspiration and predecessors, Mia Behrens and Johanne Holm-Jensen mention the social housing project of Elemental in Quinta Monroy, Chile, as well as the mini house concept of Mette Lange or Peter Friberg’s summer house in Ljunghusen, Sweden (among others). Of course one could extend the list, for example with Stefan Eberstadt’s «rucksack house» from 2004. The conceptual artist developed a parasitic construction, which is docked onto existing houses at a dizzy height and uses their infrastructure. Basically Eberstadt designed habitable sculptures and set the benchmark for change in our cities. The steel pipe cage cladded with birch plywood, the Rucksack House, was even exhibited at the International Architecture Biennial in Venice in 2006.

Rucksack House

Photography: Stefan Eberstadt

Many designs hover between an American luxury trailer home and high-tech dacha, which wanted to turn living in four walls on its head over the last 15 years. However, apart from Japan, where mini houses are part of street architecture, the concept is not really taking off, regardless of whether it’s «Su-Si» by Johannes Kaufmann from Vorarlberg, Austria or «Cocobello» by the Munich architect Peter Haimerl. So far in any case the simple summer house remains a fascinating dream. And all the pavilions and temporary structures, which express nomadism and the simple life, remain interim solutions, which hardly have any space under building law and not at all in the planning of investors, who are building for the «market».

What remains is the knowledge that the future of yesterday still comes across as begin slightly grander than current experiments – even 50 years ago the Finnish architect Matti Suuronen designed something like the mother of all lightweight constructions with his «Futuro» – a UFO, in which one could easily imagine a crazy party taking place. However, the party is over. Instead the housing shortage – which has not been a problem in Europe for a long time – has returned. And with it the question of how architects, politicians and planners should deal with it. «Architecture should be flexible, simple to build and affordable, without adversely affecting quality», demands Mia Behrens and with the open-source project «Building Blocks» is actually opening a window onto a world in which everyone can realise their dream home, as long as there is somehow a CNC milling machine with Internet access standing around. That is the first step. We will all have to make a second, third and fourth.

Movie: Jay’s Tiny House Tour