Sustainable living

NICOLE GUTSCHALK • 28.02.2019

Urban Farms –

the triumphal procession of urban agriculture?

Agriculture must continually increase the volume and speed of production to feed the constantly rising urban population. Will urban farms be able to stop the destructive exploitation of our natural resources? A review of the situation.

The forecasts are very clear: Our cities are plainly the living space of the future. Many scientists are therefore predicting that approximately 70% of the world’s population will be living in urban centres by 2050. In other words, this would be two out of three people on our planet. By the end of the century there are expected to be 10 billion cities worldwide. But already today – incidentally for the first time ever in the history of mankind – half of the population are living an urban life. Is this reason enough to be suffering nightmares? Imagining horror scenarios of over-populated metropolises, which are choking in smog and traffic chaos and will no longer be in a position to supply their inhabitants with food?

70% of the world’s population will be living in urban centres by 2050

Luckily there are people on our planet, who are working out clever solutions for the cities of our future. They are for example asking the question of how clean drinking water and clean energy supplies can be provided and at the same time protect the environment. They are thinking about what mobility might look like in the ideal cities of the future. Or they are racking their brains about how cities can be supplied with food in the future, without the destructive exploitation of our environment. Because this is certain: Already today people in cities throughout the world depend on agricultural production. On a continual increase in the volume and speed of production, which can only be achieved with the use of pesticides, fertilisers and enormously high consumption of water. The WWF has calculated that worldwide every minute 19 tonnes of the food produced for us ends up in the rubbish bin. It’s also a fact that about 1/3 of agricultural produce rots during transportation every year. All this is then called food waste. According to investigations by Foodwaste Schweiz, in this country three million tonnes of food ends up as waste every year. Just to make things clear: This would correspond to approximately 12.5 billion Olma bratwurst sausages! How are we therefore going to manage to find our way back out of this dead end? Out of this one-way street, in which a rapidly increasing urban population seems to be diametrically opposed to food production that uses resources sparingly?

One person, who has been looking into these questions for over 20 years, is the environmental scientist Dickson Despommier from New York University of Colombia. He’s also called the «Pope of Urban Farmers». «At some point in time we will run out of resources. And when cities become so large that they can no longer feed their inhabitants, the system will collapse», says the scientist, who is almost like a preacher in his popular Ted-Talks. Despommier’s solution seems simple:

Food should in future be grown where most people live - namely in the world’s cities and metropolises.

This will avoid long transportation routes and also provide freshness and transparency in production. The type of people, who are already feeding themselves as locally as possible now or at least with regionally produced food, are called «Locavores» – local eaters. A trend, which is often understood as a refined urban trend. As a movement, which enables city dwellers to rescue a bit of the environment, while decreasing their stress levels and building up social contacts. However, «urban farming» is anything but a luxury form of employment for city dwellers who are suffering from stress.

The cradle of «urban farming» can be found in the poorer districts of the world. Such as in the New York of the 1970s. At that time community gardens were created above the roofs of Brooklyn for the locals. However, something that was originally conceived by the city’s administration as a release from social hotspots, quickly developed into large-scale greening: Building façades and roofs were greened up together with planting on brownfield sites in guerrilla-like campaigns. In the meantime there are over 800,000 self-sustaining gardens in the US metropolis, which will also play an important role in the development plans of the city of New York for the year 2030. For example, according to calculations in the Big Apple, if all the urban potential is used optimally, approximately 700,000 people can be fed from local produce. The fact that a virtue can be made from necessity is also shown by the residents of the city of Detroit. Targeted de-industrialisation, in other words the move of the Motown factories away from the former city of cars, had disastrous consequences for the inhabitants: Anyone who could, moved away, anyone who stayed had to expect to be unemployed. Within a few years the entire infrastructure collapsed: Shops and supermarkets moved to the suburbs, food supplies were limited to convenience products from petrol stations or kiosks, fresh fruit and vegetables were a rarity. Until in the 1990s some residents started to use brownfield sites and grow food for themselves and the neighbourhood. Within a few years this example created a precedent. There is now a network of over 1,200 «urban farms» in Detroit. Some are only a few dozen square metres in size, others several hectares. A few are run privately, others by neighbourhoods and cooperatives.

However, most cities do not have to battle emigration or have insufficient brownfield sites, and are dealing with the very different problems of overcrowding. This is now reason enough for research in the field of «urban farming» to go a step further:

«If urban areas represent a rare, expensive good, then there really remains only one option: To move growing vertically»

Dickson Despommier, US scientist

In other words in enclosed spaces, in which the plants thrive without any soil and are specifically fed with nutrients and manage with only a tenth of the amount of water, which they usually require in conventional farming. The indoor plants receive radiation from LEDs in different wavelengths so that photosynthesis is triggered. Where we seem also already to have reached the crucial point in the track record of urban farms: According to a large number of investigations, such vertical greenhouses are not currently really competitive compared with conventional farming in fields and in normal greenhouses because of their high energy costs. For example the German Aerospace Center (DLR), calculates that at present 1 kilogramme of food produced by an urban farm at our latitude, would cost about EUR 12. Definitely too expensive to feed 7 billion city dwellers.

Apart from the high energy costs, there are also cities on our planet, in which a concentration on urban agriculture makes little sense. This is well illustrated by the example of Switzerland: The project by the Zurich start-up company Urban Farmers, which was started with a great deal of enthusiasm and many plans for expansion in the Dreispitz area of Basel, had to close down last year. The initiators of the scheme had placed their faith in an interesting and extremely sustainable method: aquaponics. A natural circulatory system, which connects fish farming with growing vegetables. However, the investment was too large and the income too small. Another reason for the failure of the project can be attributed to its location: Because in this country almost every farmer is an urban farmer. The closest farmyard can often be reached on foot from an urban supermarket.

But the situation is very different in mega-cities such as Singapore, which is mainly dependent on imported goods. On the island country food is purchased from Malaysia, Thailand or China and can spend up to a week being transported. The fact that in Singapore sustainability would at some point in time become a matter of survival was recognised at an early stage by the city’s administration and it therefore had already specifically invested in urban cultivation projects 30 years ago. In the meantime the island state is a long way ahead as far as urban farming is concerned. The magic word is: Go-Grow. A system, which is based on rotating levels that are on top of each other. All the levels being cultivated in the vertical farm receive the same amount of sunshine through the rotation. This is because one thing is certain in Singapore: Constant sunshine – an advantage, which we cannot benefit from in northern latitudes.

If in future urban farming is also to gain a foothold in our latitudes, we have to hope for sustainable and favourable forms of energy.

Urban farming projects

Six project examples

from all over the world

London

33 metres underneath the streets of London lettuce and a large number of herbs have been growing in a post-apocalyptic environment since 2015. However, there’s very little evidence of the romantic charm, which is implicitly implied by the term urban gardening, in the Growing Underground scheme: Here it’s more like a spaceship. The plants are stacked on top of each other in the tunnels of the unused air raid bunker in sophisticated hydroponic shelving systems and are illuminated with LEDs. Growing-Underground.com

Paris

In the Paris suburb of Romainville a vertical agricultural project is currently being created, which is intended to transform urban agriculture into a «Vegitecture» complex, whose production circulatory system will enable the inhabitants to obtain products directly from their local urban farm. In a glass greenhouse on several floors covering an area of 1,000 square metres, the French architecture office Ilimelgo wants to house plants in a system, which maximises the sun’s radiation and natural ventilation.

Berlin

Freshwater fish (perch) are being bred in collected rainwater in an old factory building in the Berlin agricultural project called ECF Urban Farms. The water enriched with fish excrement is subsequently used to grow vegetables in the greenhouses. The advantage of this so-called aquaponic system is that it is more or less a closed water circuit: Production takes place close to the consumer and there is no need for transport. The waste product of fish production is in turn used as fertiliser to grow the vegetables. The company produces about 30 tonnes of fish and 35 tonnes of vegetables every year. Ecf-farm.de

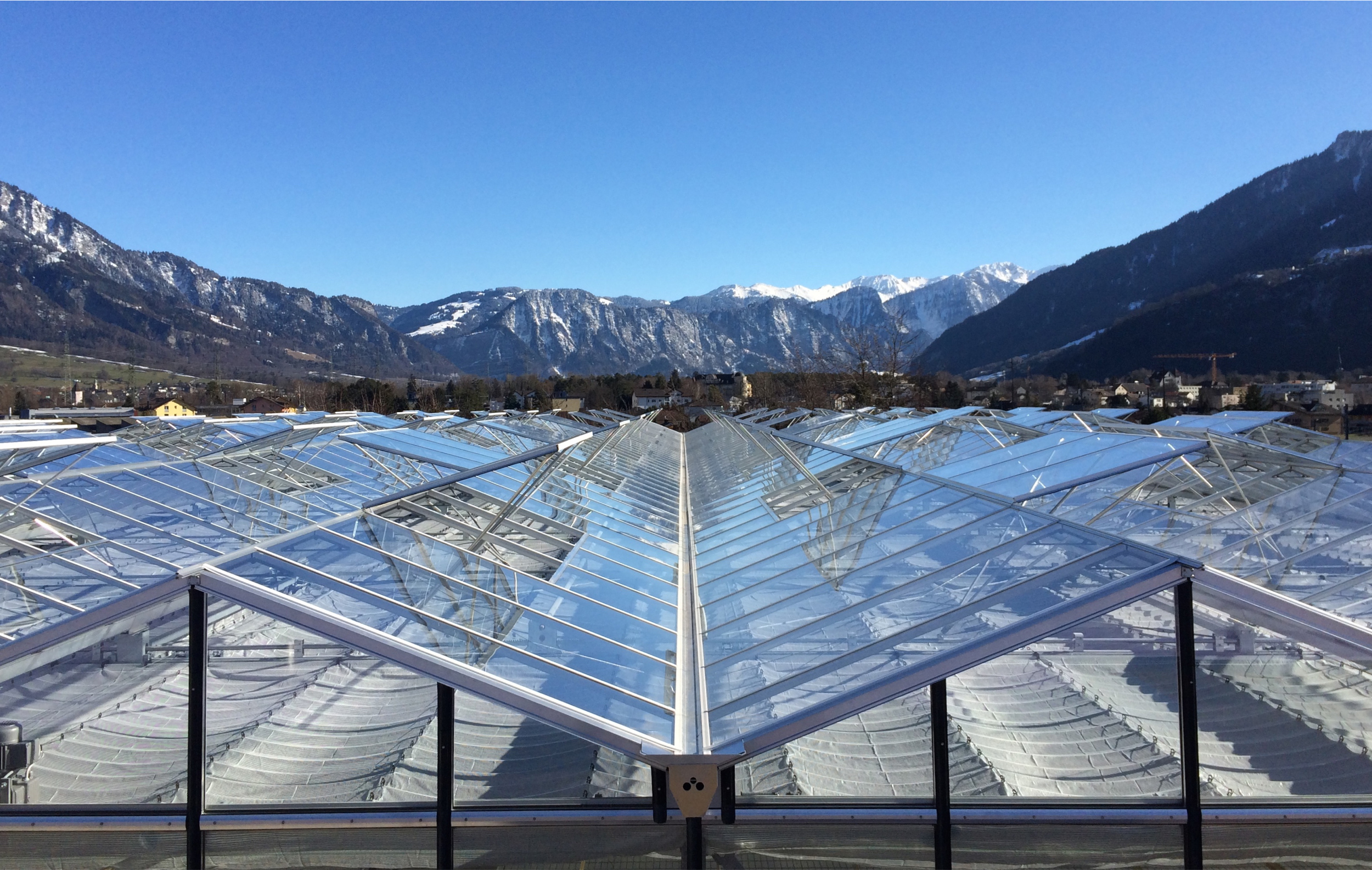

Switzerland/Bad Ragaz

The Berlin company ECF Farms has passed on the largest roof farm in Switzerland to its customer Ecco Jäger, which now runs the farm in Bad Ragaz. The facility is successful and sustainable at the same time and uses the waste heat from the cooling rooms to heat the fish tank and the greenhouse. Ecco-jaeger.ch

Singapore

©Skygreens Singapore

Sky Greens is the world’s first low-carbon, hydraulically operated agricultural business. The company offers an environmentally-friendly solution to the city for producing fresh vegetables and in doing so saves land, water and energy. Sky Greens is supported by the government of Singapore and has major plans for expansion: In future 8-9 million plants are to be grown every year on 2,000 farm towers, which are located on 3.7 hectares of land. Skygreens.com

New York/Chicago

Gotham Greens is growing fresh produce in technologically advanced, climate-controlled urban greenhouses very close to retailers and catering companies. This ensures the reliability, transparency and traceability of the entire supply chain. The company currently owns and operates four production facilities in NYC and Chicago covering a total area of 170,000 square metres. Another 500,000 square metres are at the planning stage and are intended to be introduced in five additional federal states. Gothamgreens.com