Ariana Pradal • 17.01.2019

Carpet journeys: An industry in decline

Our walls are getting thicker and our floors warmer. Do rooms still need textiles to keep out the cold? For a long time, they didn’t seem to. Since the turn of the millennium, though, carpets have slowly found favour again. And their revival has not escaped the notice of designers in Switzerland. Three new labels and a seasoned duo, who spotted the shift in trend early on, tell us how they came to create carpets.

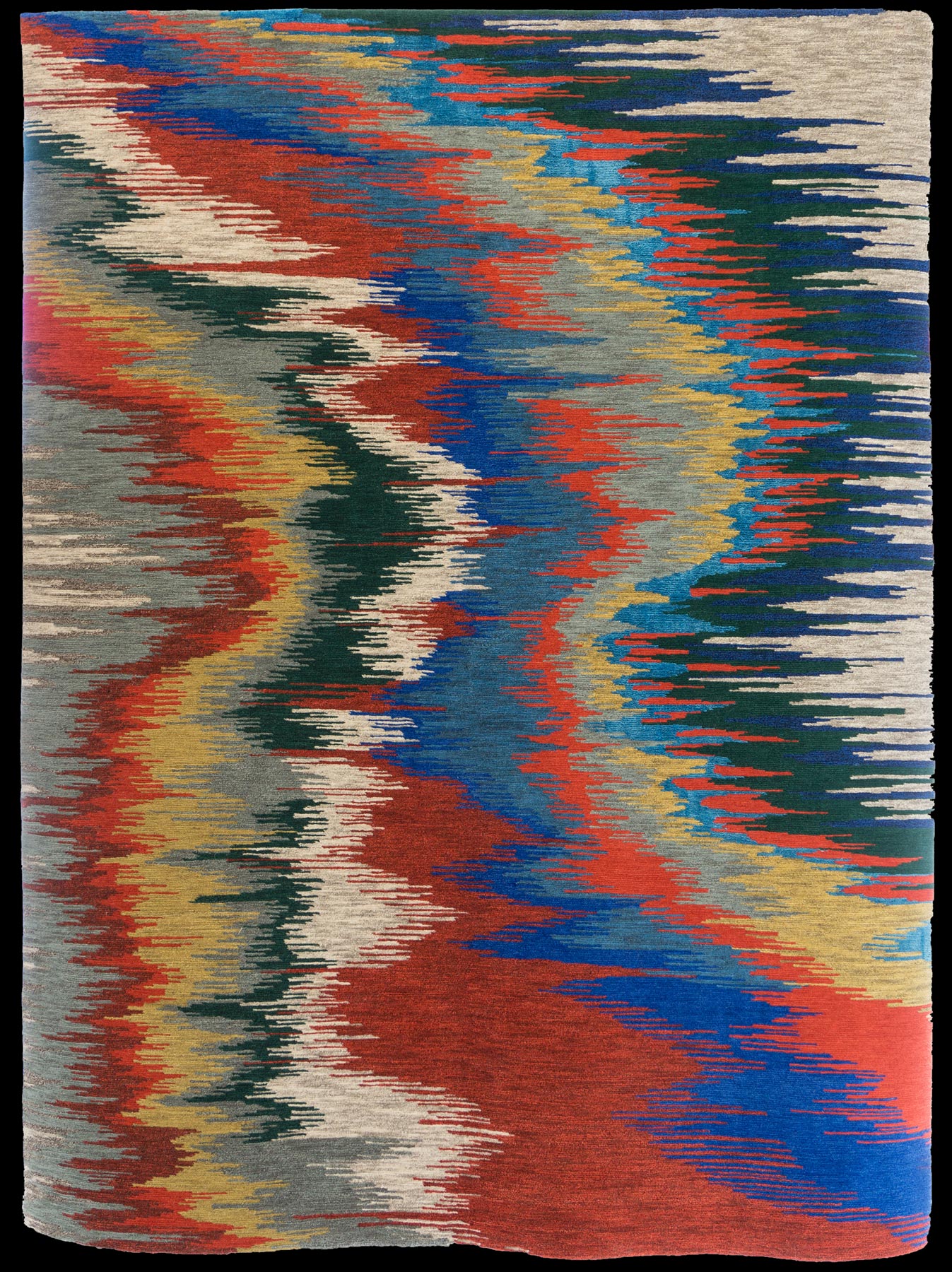

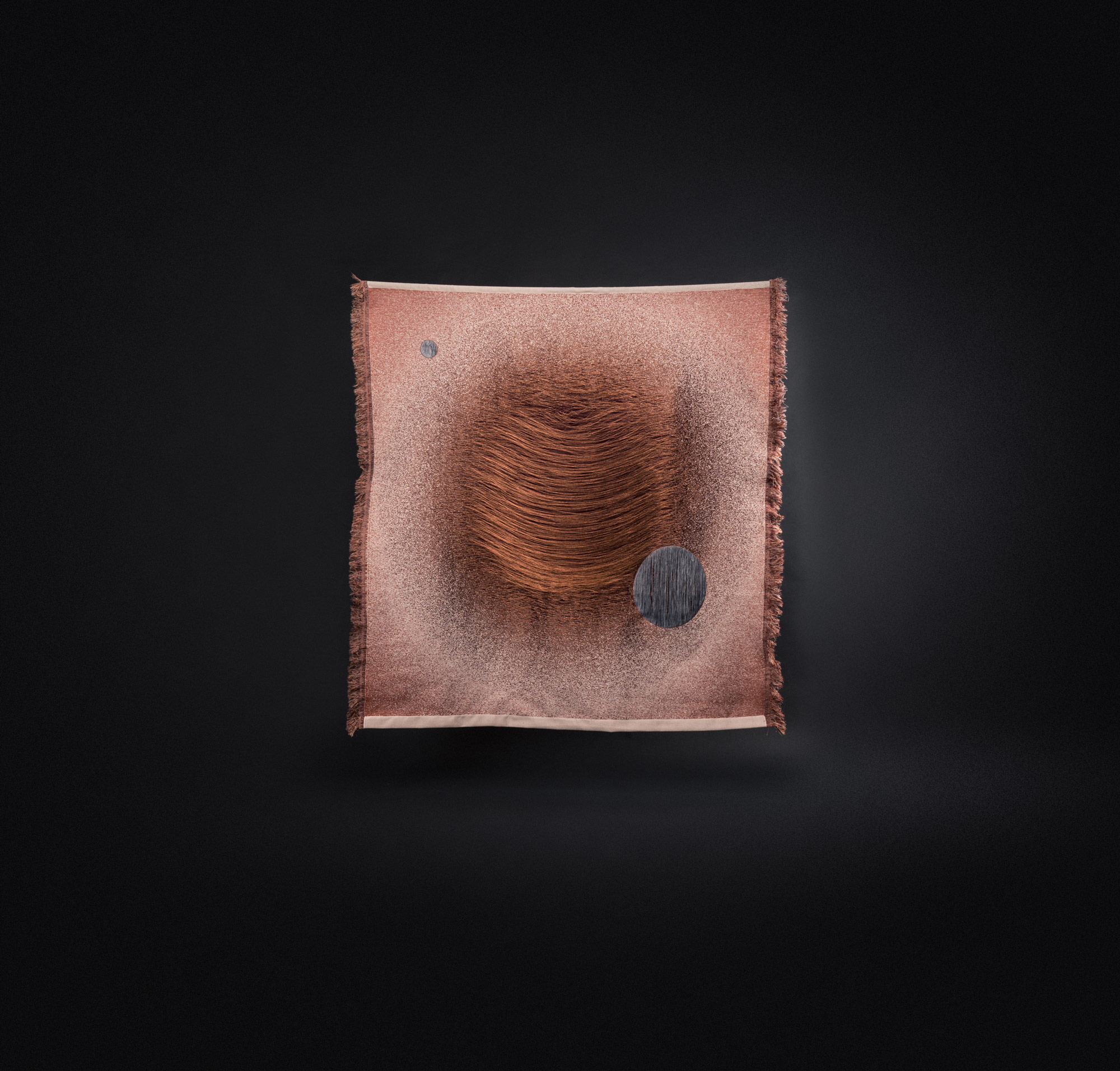

From zen to hallucinogen

Christoph Hefti’s carpets subvert any ideas of how a carpet should be – the unusual combination of motifs, of tradition and zeitgeist, or the marrying of different parts to make a new whole. Yet all of the pieces by this designer, who moves between fashion, furniture and music, are traditionally hand-knotted in Nepal. The textile designer’s expressive works also include quiet designs with colour gradients or a motif reminiscent of overlapping paper scraps or stones. “My way of designing carpets came about naturally. Around five years ago, I had the idea of making a carpet and seeing where it took me. Without realising it, I was probably looking for an alternative to fashion”, is how Christoph Hefti sums up the start of his carpet journey. After decades of designing textiles for the fashion industry, he wanted to try something new and more craft-like.

«My carpet project usually awakens a rather allusive yearning among people here in Europe. It inspires them to think about travel, about being creative, and so on […]»

Christoph Hefti keeps going back to manufacturers in Nepal for his carpet creations. He looks for partners there and then. Some of the designs he prepares; others are created on location. “My carpet project usually awakens a rather allusive yearning among people here in Europe. It inspires them to think about travel, about being creative, and so on. But the reality is different – you have to be tenacious and not give up. It’s an unpredictable business, involving a lot of money, because the investments are high”, the textile designer summarises his experiences. The busy designer adds that there can sometimes be lovely surprises that are then followed by a series of disappointments.

But such is his enthusiasm for this object that he keeps going nonetheless. “I’m fascinated by the tradition and culture of carpets, and they also give us lots of ways to design our spaces. A carpet can take us on an exciting journey away from our rather dull range of tastes. Like losing yourself in a book, but with colours, shapes, textures and materials.”

When Christoph Hefti started making carpets, he didn’t know how to organise sales. But then, he found Galerie Maniera in Brussels, which takes part in international trade fairs such as Design Miami Basel, and sells his works to collectors, interior designers and design lovers.

From Bern to Morocco

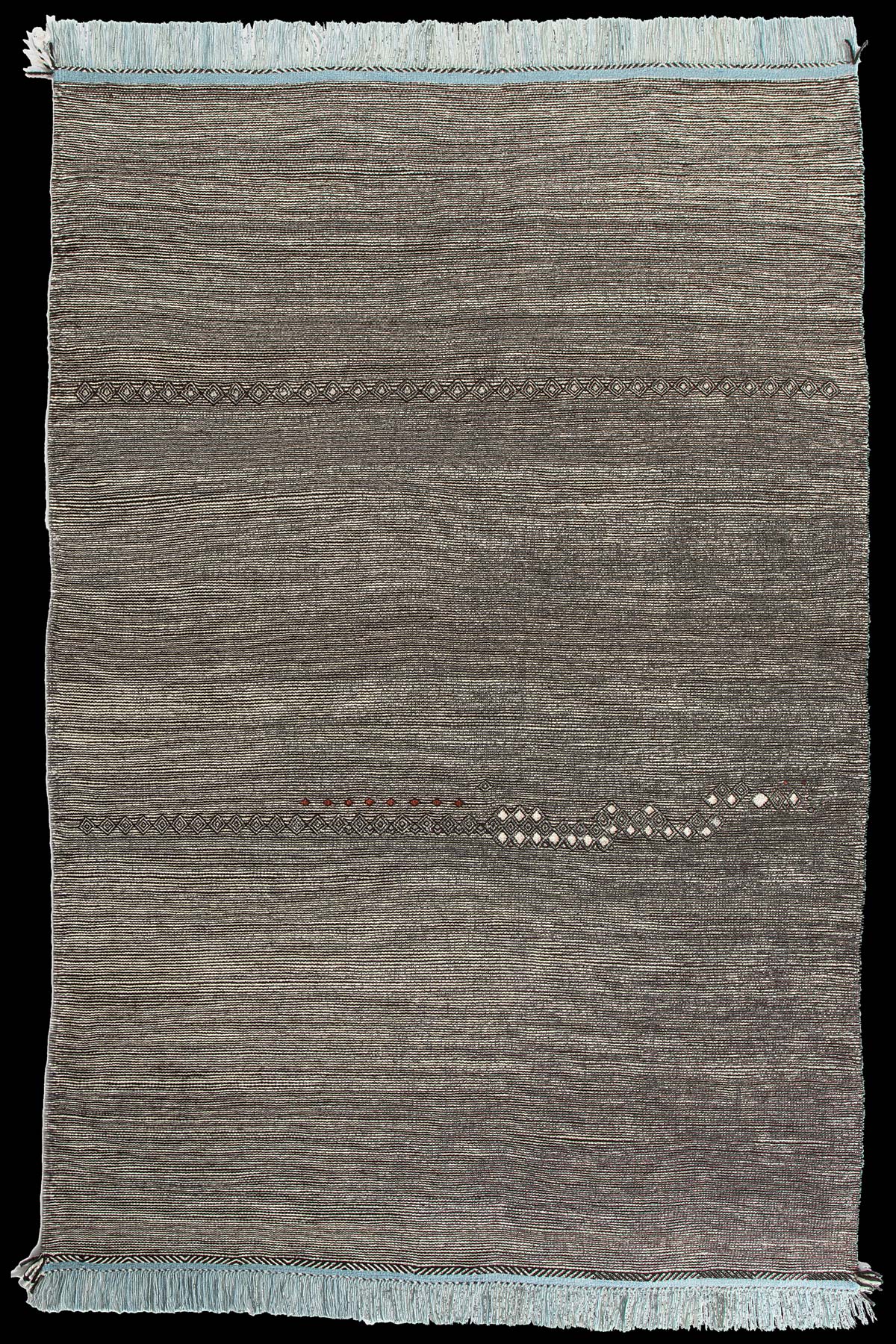

Hung, stacked and rolled – Salomé Bäumlin’s presentation of her contemporary works in her showroom on the outskirts of Bern almost resembles that of a traditional carpet store. The textile designer is in a hurry. She is travelling back to Morocco tomorrow to take delivery of finished carpets in her designs. “The carpets were actually supposed to be finished weeks ago, so that I could present and sell them at various trade fairs. But the Berber women who do the weaving and knotting for me don’t care about delivery times.” This realisation clearly illustrates how the Bernese woman moves between very different worlds. “Before my textile design training, I studied art. I still see carpets as being pictures in a room. Because we sit, stand or sleep on them, the users also become part of the picture”, the business woman explains how she sees this piece of furniture. Salomé Bäumlin’s carpet journey began as a master’s thesis at the Lucerne School of Art and Design. She had the first prototypes made in Morocco at the end of 2013. Today, around 50 Berber women from various tribes work in Morocco’s hinterland for her carpet label Ait Selma. The women weave and knot at home, on their traditional looms. They look after the children and animals and, when time allows, they make carpets. “More women would like to work for me. But, for that to happen, I would have to improve distribution and sale”, says the designer. Like so many creatives, though, this isn’t the aspect that excites her.

«Before my textile design training, I studied art. I still see carpets as being pictures in a room. Because we sit, stand or sleep on them, the users also become part of the picture»

Many of Salomé Bäumlin’s designs are black, white or grey. The carpets from her five, ever-growing collections are characterised by lines and geometric patterns. These colours come from the natural sheep’s wool that the Berber women spin into yarn. “Many of my designs are simplified versions of traditional Berber patterns – fewer colours and fewer shapes. That way, Ait Selma rugs bridge the gap between the culture of the makers and the buyer”, explains the textile designer. Salomé Bäumlin’s carpet journey is closely linked to social responsibility and sustainable production. Her orders give Berber women an opportunity to earn money at home. At the same time, the traditional craft, from wool spinning to finished carpet, is preserved.

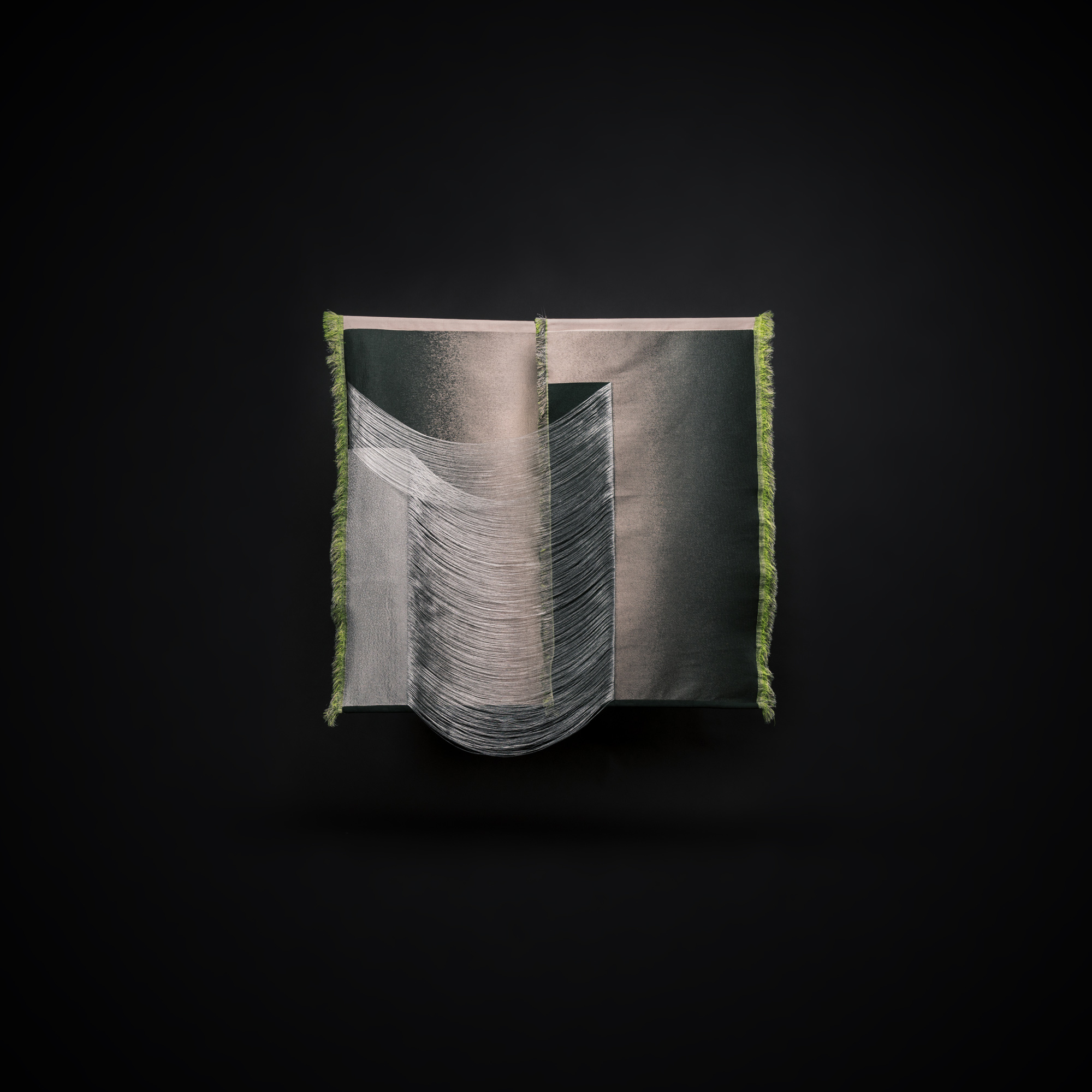

From two to three dimensions

Carpets used to be designed not just for floors, but also for walls. But who wants tapestries these days? Young textile designer, Marie Schumann, works on the border between the two – her designs can be hung on the wall or in the room. What at first seems outdated becomes fascinating the moment you see and touch the creations that Marie Schumann calls “Softspace”. The fabrics that she lets down here and there look delicate and elegant. A single thread or a whole row of threads come away from the fabric and are pulled down by gravity. Bend the Softspace to create a thread sculpture. Are her works wall hangings, room dividers, or neither? “I call my works spatial fabrics or textile design objects”, explains the designer. “I created Softspaces 1 to 7 for my masters’ thesis at Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts. I didn’t have a destination in mind, but more of a journey”, laughs Marie Schumann. She came about these textiles, whose effect and feel really are captivating, through experimentation and intuition. Marie Schumann is interested in the atmospheric qualities of textiles in a space. The interplay of architecture and fabrics. It is therefore entirely possible to imagine her Softspaces in a larger dimension or more closely linked with architecture. The designer has so far only produced one piece for each of her designs – 18 Softspaces have already been realised and five will be finished in the near future. They have all been made either at Tisca Weaving Mill in Bühler, Appenzell, or at TextielLab in Tilburg, Netherlands, on a Jacquard loom. But digital code would allow a larger number of units per design or different colours or material variations on the same design. The designer is thinking about these questions at the moment, as she prepares for the Salone del Mobile, Milan.

We spoke to the pioneers

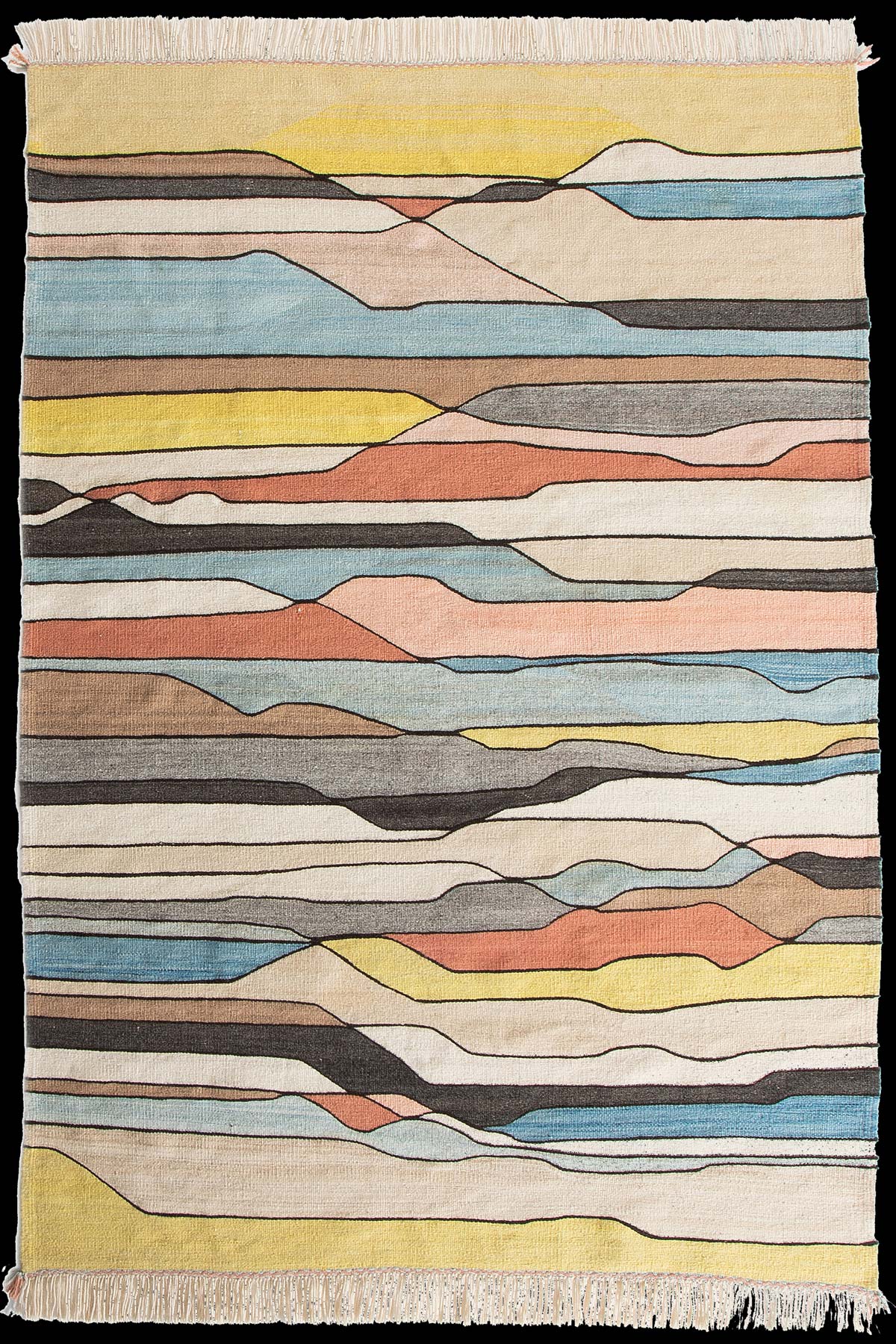

Hugo Zumbühl and Peter Birsfelder founded their Teppich-Art-Team in 1998, when carpets in new designs and materials were slowly becoming popular again. The duo always use surprising materials in their designs, such as used jute coffee sacks, worn-out clothes, or combine hemp yarn with PVC yarn. The label has just celebrated its 20-year anniversary. That’s reason enough to ask Hugo Zumbühl how it all began and how things are today.

How did you and Peter Birsfelder come up with carpets?

Peter was master weaver at Thorberg prison for many years. I trained at Zurich University of the Arts, and worked for a few years as a technical adviser in a craft cooperative in the Peruvian Andes. One of the areas I worked in was hand weaving.

What are the stand-out features of your collection?

We try to express a contemporary attitude in our products and to achieve a consistent material aesthetic and quality. We really value transparency in production, as well as social and cultural commitment. The materials are specially manufactured by small workshops, at fair prices. The carpets are made in our own hand-weaving mill or in the workshops of Swiss social institutions.

How do you organise manufacture and distribution?

Peter is responsible for technical implementation and quality. I’m responsible for design and distribution. Distribution is done through dealers. To begin with, we worked directly with Swiss furniture stores. Global trade was done via carpet company Ruckstuhl for ten years and some of it still is today. In recent years, we have mainly sold our products at our studio in Felsberg (GR) and at various design fairs. We have recently also sold products through Okro-Konzepte in Chur.

Your market?

Our products always attract a lot of interest at design fairs. Unfortunately, this often doesn’t result in sales, because of the high costs. As a consequence, you can only afford to work in this field part time if you want to survive.

Insight IKEA:

IKEA launched a special rug collection at the beginning of the year. Eight artists from all over the world came up with eight very different designs. Wild creations are now definitely the thing to have.